Money Chasing Deals

Dan Gray on why private markets are horribly inefficient

Hi there, Patrick Ryan here from Odin - the seamless way to raise and deploy capital in private companies, used by over 10,000 VCs, angels and founders globally.

Today a guest post from Dan Gray (@credistick), followed by some commentary from yours truly.

There are two types of VC:

1) busy complaining / thinks VC is about access

2) busy investing / knows VC is about outliers

The phenomenon experienced by the first group is called “money chasing deals”, and has been the subject of study going back to the 90s.

“First, the analysis shows that inflows into venture capital funds have had a substantial impact on the pricing of private equity investments. [...] Consistent with predictions, the impact of venture capital inflows on prices was greatest in states with the most venture capital activity and segments with the greatest growth in venture inflows.

Second, we show that the relation between increased fundraising and prices does not appear to be due to greater perceived investment prospects.”

Source: “Money Chasing Deals?: The Impact of Fund Inflows on Private Equity Valuations”

VCs find a vertical they like and it starts to get “hot”.

The herd piles in - bigger rounds, monster markups, overnight “successes”. All without any material impact on the underlying value of the companies.

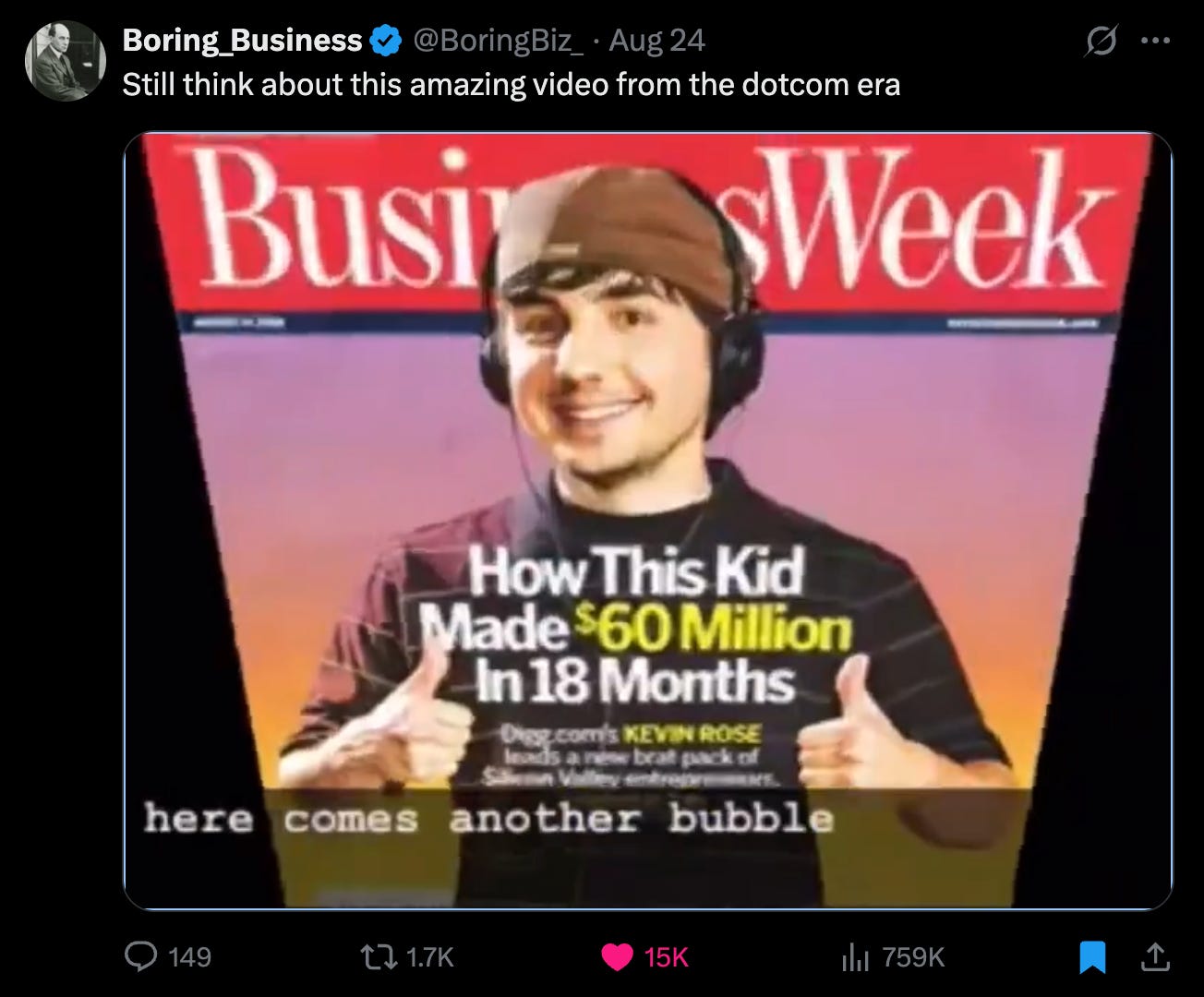

It’s a recurrent structural problem in VC and leads to boom and bust cycles that, more often than not, incinerate a whole lot of cash and leave us with very little to show for it.

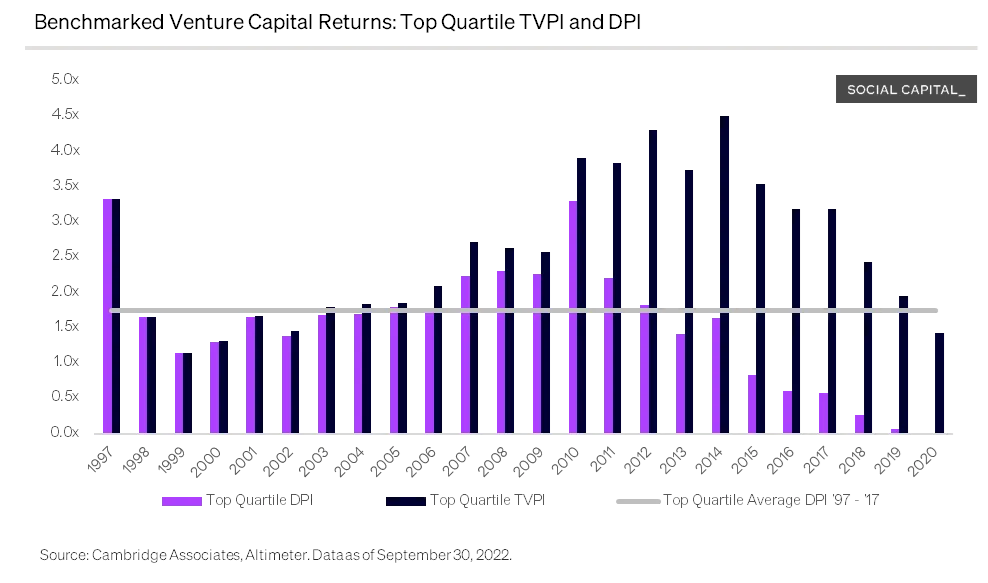

This is most obvious in hindsight. The bubble burst in 2000, but the impact was felt on vintages as far back as 1997. By the 1998 vintage, performance had already fallen off a cliff.

Excellence in investing requires bravery.

Were you brave enough to hold Amazon when its stock crashed 90% during the bust?

Or brave enough to back a non-consensus dotcom bet like Google? When they launched in 1998, search was considered by many to be a solved, stagnant category.

Perhaps you were brave enough to avoid the sector altogether? The following giants were all started in that same period. Many would likely have taken/ your money at a very competitive valuation:

- BYD (1995), batteries [at the time] - ~$107bn turnover 2024

- Lululemon (1998), clothing - $9.1B turnover 2024

- Intuitive Surgical (1995), medical devices - $8.35B turnover 2024

- BioMarin Pharmaceutical (1997), biotech - ~$2.85bn turnover 2024

- Seagen / Seattle Genetics (1997), biotech - ~$2.3bn turnover 2024

Unfortunately, in the heat of the moment, none of those options aligned with the incentives created by eager LPs, arriving late to the party with sacks of cash.

The same steps play out every time, as the supply of capital increases:

more capital → higher prices → greater expectations → multiple expansion → overcapitalisation → market crash

All without any implicit increase in quality or potential of the underlying investments.

A very simple way to avoid this trap is for VCs to develop a better understanding of valuation (not “pricing”), so they may recognise when the market transitions to truly irrational behavior. This is easy for the non-consensus investor, since price increases are mostly limited to consensus categories. Unfortunately, the majority of capital is not typically deployed by these investors.

The waste of a bubble is often further amplified when, for political or macroeconomic reasons, the supply of capital is greater, and the apparent supply of other opportunities is lower:

“Increases in venture fund-raising which are driven by factors such as shifts in capital gains tax rates appear more likely to lead to more intense competition for transactions within an existing set of technologies than to greater diversity in the types of companies funded.”

An obvious recent example of this is the enthusiasm for Web3 in 2021, driven by a perfect storm of ZIRP, Covid boredom and technological stagnation.

Thus, one of the tragic paradoxes of venture capital:

- When capital is most abundant, it is usually being put to work by opportunists - money chasing deals. Very little value is created.

- When capital is most restricted, it is usually put to work by competent investors. Lots of value is created.

Ideally, and obviously, you’d want the capital abundance in the hands of the competent investors, but that’s just not how venture capital has been structured.

What does this mean for us today?

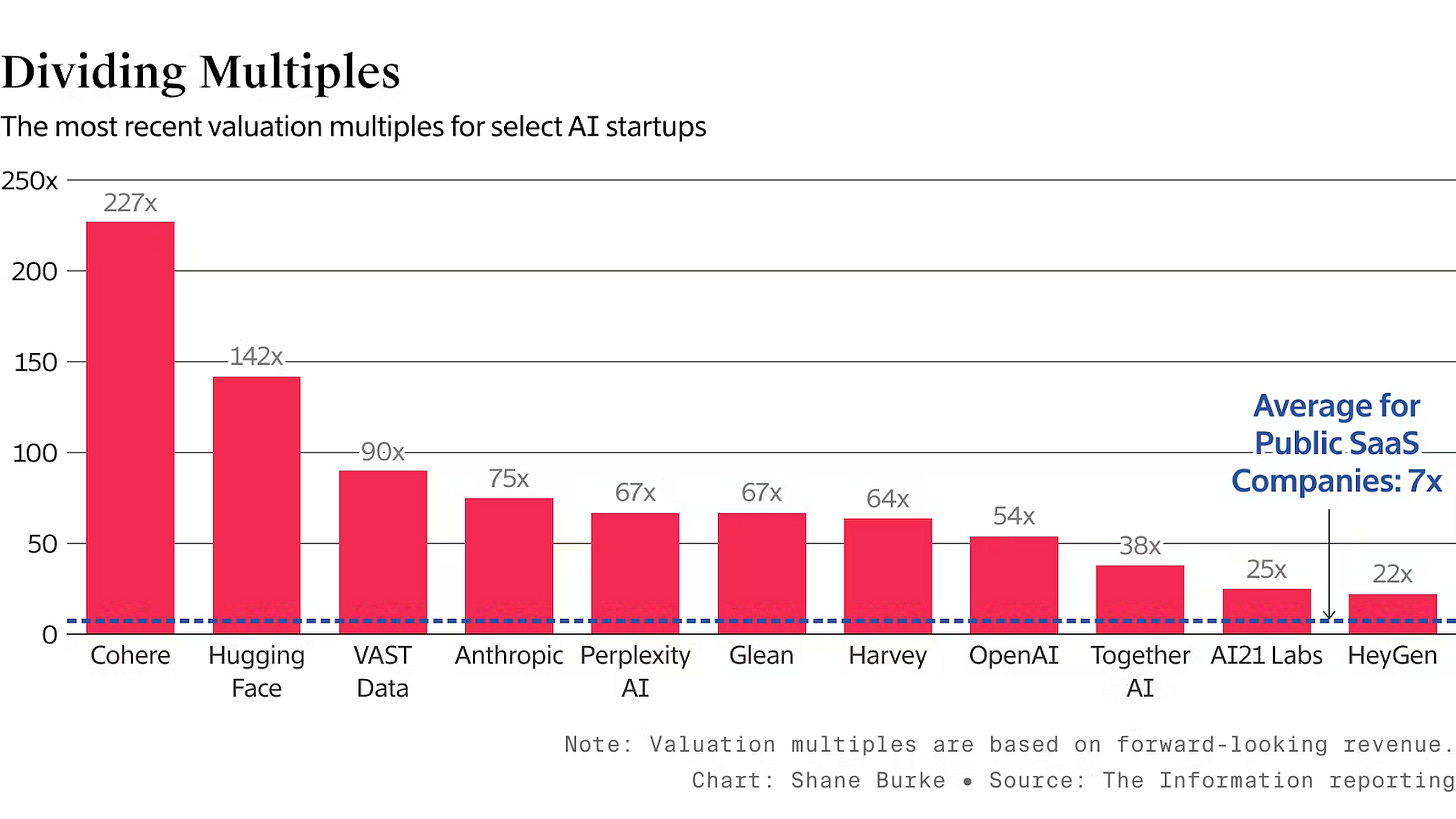

Things certainly look a bit spicy, don’t they?

We can discuss when the bubble might burst, if it’s a good bubble or a bad bubble, etc.

I don’t think this is particularly useful or novel.

A more interesting question to ask is “how might this play out over the next 10-15 years, and what does it imply for us today?”

Personally, I sit in the same camp as Nicolas Colin, Andrew Cote and Jerry Neumann.

As Jerry puts it, “AI will not make you rich”.

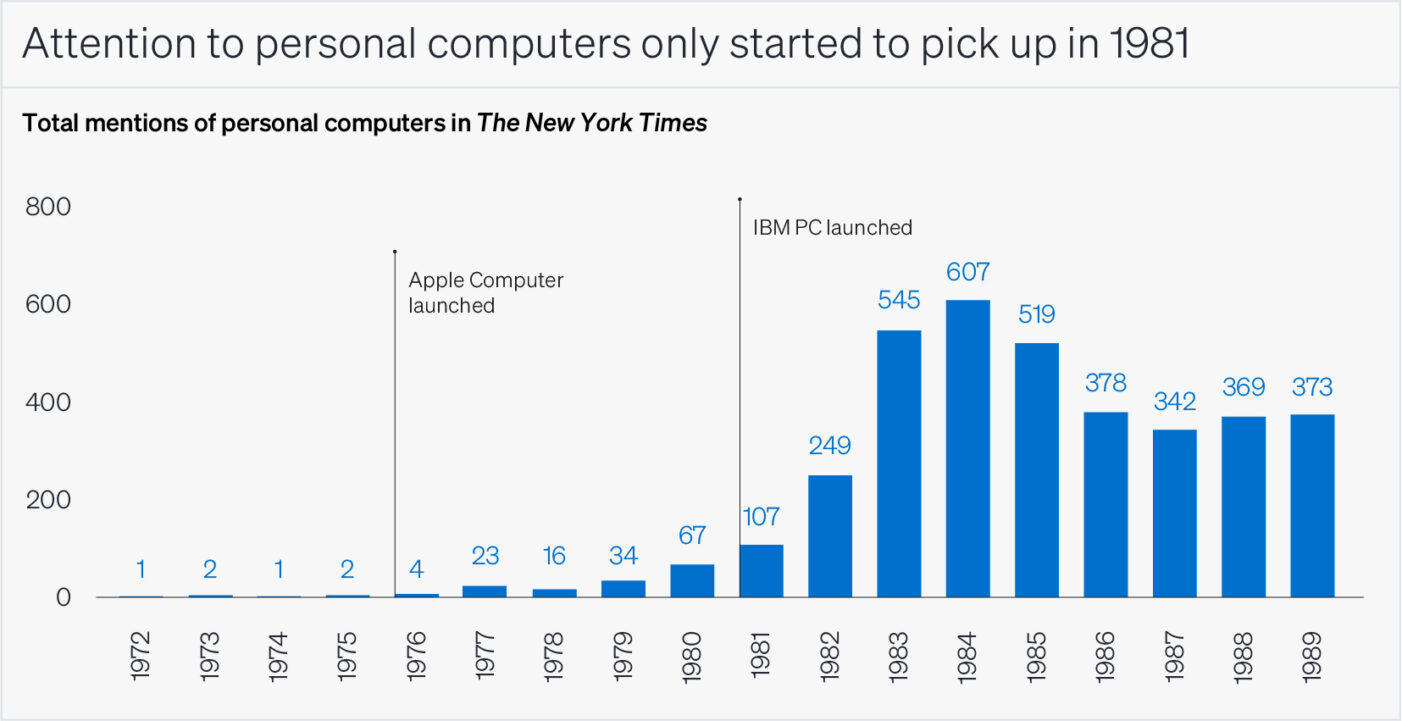

When Apple launched their first computer, nobody gave a shit about computers. Even 7 years later the hype was only getting going.

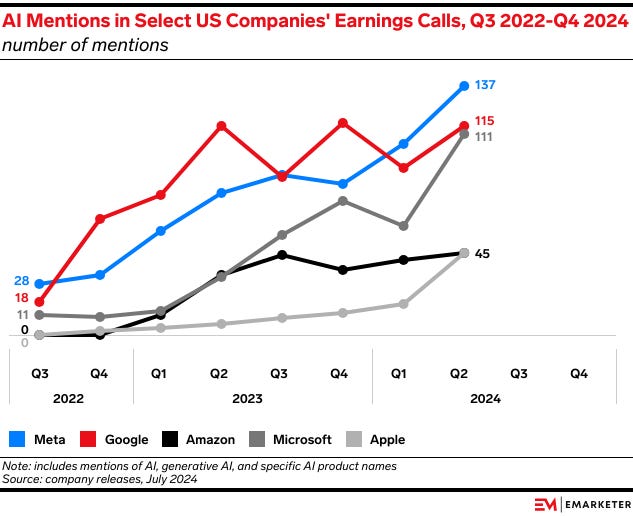

In contrast, the entire world is talking incessantly about generative AI, and has been since ChatGPT launched. Everyone sees and understands its potential.

More importantly, the incumbents have cottoned on quickly to the opportunity and are capitalising on it - i.e. they’ve beaten the Innovator’s Dilemma.

This isn’t the sort of highly uncertain arena that VCs tend to make real money in.

In fact, the argument goes, Gen AI is the opposite of a revolutionary technology.

We are eking the final efficiencies out of the tail-end of computing’s great technological cycle, which was kicked off by the invention of the transistor in the 50s and the microprocessor in the 70s. It boomed with the internet in the 90s, and there were still great returns via SaaS and mobile apps from 2000 to today.

But information technology is now a well-understood area of the economy. Uncertainty and risk are low. The big winners of the information era dominate the global economy completely; the Magnificent Seven represent ~35% of the value of the S&P 500. This game is won.

It is, therefore, not in a place where speculative capital has nearly as much opportunity to make outsized returns.

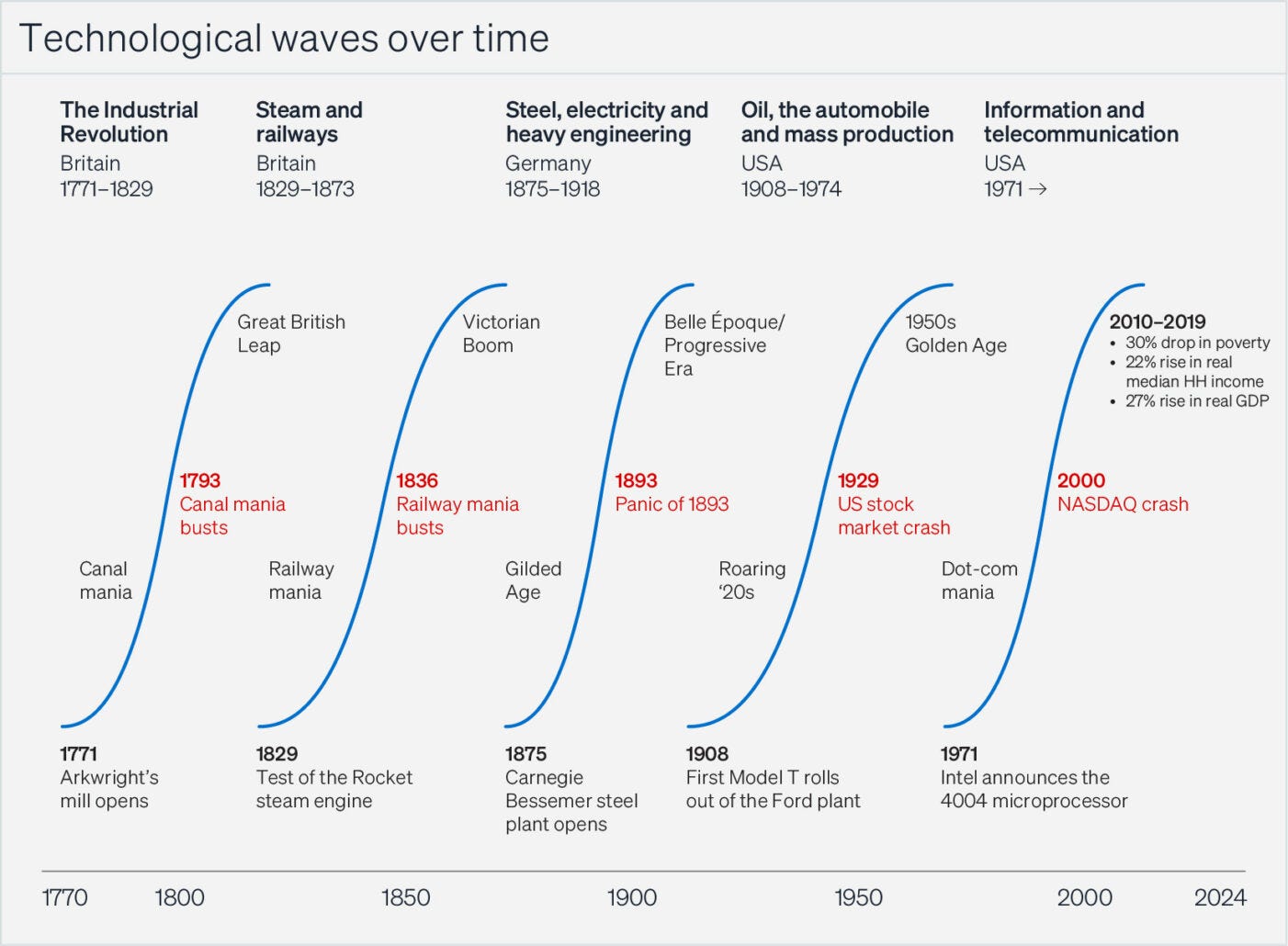

This is a predictable pattern that previous technological booms have followed, as famously highlighted by Carlota Perez (every VC thinkboi’s favourite writer):

This macro cycle typically plays out over 50 -70 years.

First, a revolutionary technology gets early adoption in niche circles. Over a period of 20 - 40 years, speculative investment by risk-on investors follows, driving widespread deployment of the technology. This eventually leads to overinvestment and ultimately, a big collapse, after which the technology continues to spread and make its impact felt, but eventually matures into a commodity.

Each collapse - marking the shift from extraordinary returns to more average ones, more in line with the rest of the capital markets - lays the foundation for the next wave of innovation. What was once cutting-edge becomes part of the commoditised, background infrastructure that enables the next great technological “irruption”.

For example:

Industrial Revolution → Steam Engine & Railways

Steam Engine & Railways → Steel, heavy manufacturing and electricity

Steel, heavy manufacturing & electricity → Oil, the automobile, mass-production, telecomms

Oil, the automobile, mass-production & telecomms → Information Technology

“If I had asked people what they wanted, they would have said faster horses”

Think about who invented the transistor in the first place - it was created at Bell Labs in 1947. Bell Labs was the moonshot lab of a telecoms monopoly - winners of the previous cycle. It was also only possible for the computer to revolutionise the world because we already had mass production, plastics and telecomms.

Similarly, Henry Ford started his career at Edison Illuminating Company of Detroit (winners in electricity). After his promotion to Chief Engineer in 1893, he had enough time and money to devote attention to his experiments on gasoline engines. These experiments culminated in 1896 with the completion of a self-propelled automobile, which he named the Ford Quadricycle.

But is Gen AI like the Ford Quadricycle, or is it more like “faster horses”?

Let’s think about it.

Gen AI’s best use cases are

1. Writing, and

2. Producing audio, images & video

This allows you to do two things well:

1. Make more software, and

2. Make more content.

It actually does both of these things quite badly right now, but it’s getting much better over time.

Gen AI therefore represents the commoditisation of software and online media, the two “highest leverage” technologies of the last 40 years. It doesn’t give us anything fundamentally new so much as it gives us “more of the same”.

It is very hard to make money in commoditised markets.

Scale, brand and control of distribution are your only real moats.

In Neumann’s view, therefore, most of the value that generative AI creates as a technology will likely be captured by:

Incumbents (the Magnificent 7)

These are the only firms with the capital and access to data at scale to compete at the model level. They’ll swallow up most of the model startups - there will be a lot of consolidation. They also own the consumer distribution channels for model access AND for all the new content people are making.“Knowledge economy” services companies that are “content heavy” and can morph into gen-AI powered software businesses, offering the same service much better AND cheaper.

Think professional services like management consulting, healthcare, education, law, financial services, marketing, etc. Startups in these spaces will be able to disrupt and consolidate fragmented, often low NPS industries that software hasn’t eaten yet - industries that account for a third or more of global GDP.Consumers - “who should see a wider variety of knowledge-intensive goods at reasonable prices, and wider and more affordable access to services like medical care, education, and advice.”

All of this is not to say that many investors are not going to make money in AI. You can make a huge amount of money in bubbles simply by trading the bubble, for example - we are seeing a lot of secondary activity in the likes of OpenAI, xAI, Anthropic, etc. at the moment, and people are doing well. But this is trading, not investing, and it’s risky in illiquid markets.

There are also many interesting bets in bucket 2 - the “AI rollup” thesis is a bet on this trend - companies like Lawhive (legal services, backed by Balderton, GV, Episode 1), Dwelly (property management, General Catalyst), Buena (property management - GV, 20VC), Crete Professionals Alliance (accounting, Thrive), Savvy Wealth (financial services, Thrive), etc. But it’s closer to private equity structurally than VC.

My point is more that the next Elon Musk, Henry Ford, JD Rockefeller or Thomas Edison probably isn’t building a company like this. They almost certainly don’t describe themselves as an “AI founder”. They might use AI, but it’s not their focus.

What they will build is not certain. But to be revolutionary, it has to truly change the trajectory of human history and drive our progress as a species, the same way the automobile, refined petrochemicals and electricity did.

Maybe they’re in biotech, maybe they’re in energy, maybe they’re in material science - who the hell knows.

One thing is for certain; they’re a weirdo in a garage, and most people don’t know about them… yet.

Want to invest in weirdos? Launch your investment firm with Odin.

P.S. thought you’d enjoy this video

Love this!

Hey, great read as always. This 'money chasing deals' insight is so spot on; do you think well ever see a true market correction to this inherent VC structural probleme?