Ideas for Angel Investors #1: Indexing

Why rational investors should have much larger startup portfolios

Hi folks, Patrick Ryan here from Odin. We make it easier for VCs and angel syndicates to deploy capital. We take care of the paperwork so you can focus on investing.

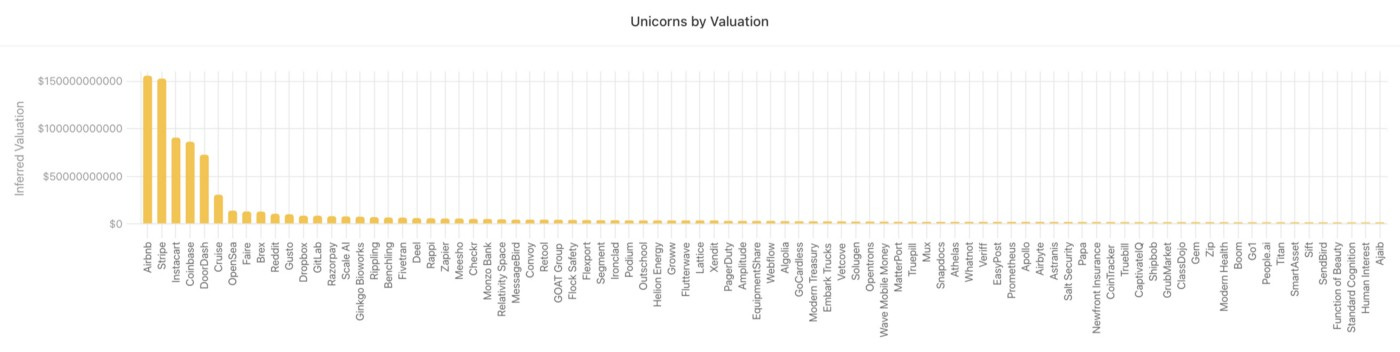

In early stage investing, outlier deals are all that matters.

As I mentioned a few weeks back, even amongst Y Combinator’s 70+ unicorns, the top 10 have produced well over 2/3 of the value.

The Power Law is so… powerful… that it actually makes statistical sense to invest in a lot of companies. Way more than you realise.

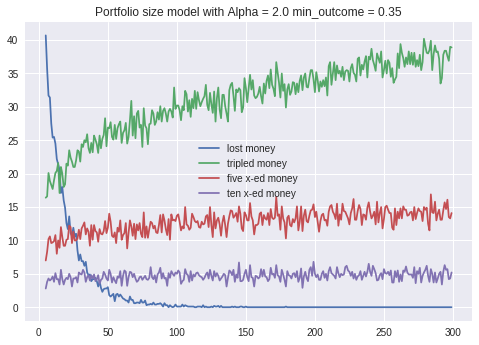

Based on some research from Steve Crossan1, you should probably aim to have at least 150 deals in your startup portfolio, but more like 300 if you can.

If you have a 300 deal portfolio instead of a 30 deal portfolio, your chance of tripling or quintupling your money is ~80% higher:

Perhaps more surprisingly, your chance of 10xing your money doesn’t decrease. The upside of a true outlier outweighs the downside risk of losing money on all the others.

Plus, as your portfolio grows beyond 30 companies, the chance of losing money altogether declines from as high as 10% to close to 0.

Research from Abe Othman at AngelList (the biggest startup investment platform in the world, with a larger dataset than any other organisation) supports Crossan’s findings:

“We did do some simulations… on what indexing at seed actually looks like over human timescales. Over a ten-year investment window, indexing beats 90-95% of investors picking deals, even when those investors have some alpha on deal selection. So the idea that there are some terrific seed investors that soundly beat indices is not inconsistent with our results.”2

This all sounds like common sense to public markets investors. It’s very similar to the strategy first promoted by Jack Bogle (the founder of Vanguard) almost 50 years ago. Indexes and ETFs now dominate the public markets.

However, “spray and pray”, as it is known, is viewed with disdain by many VCs.

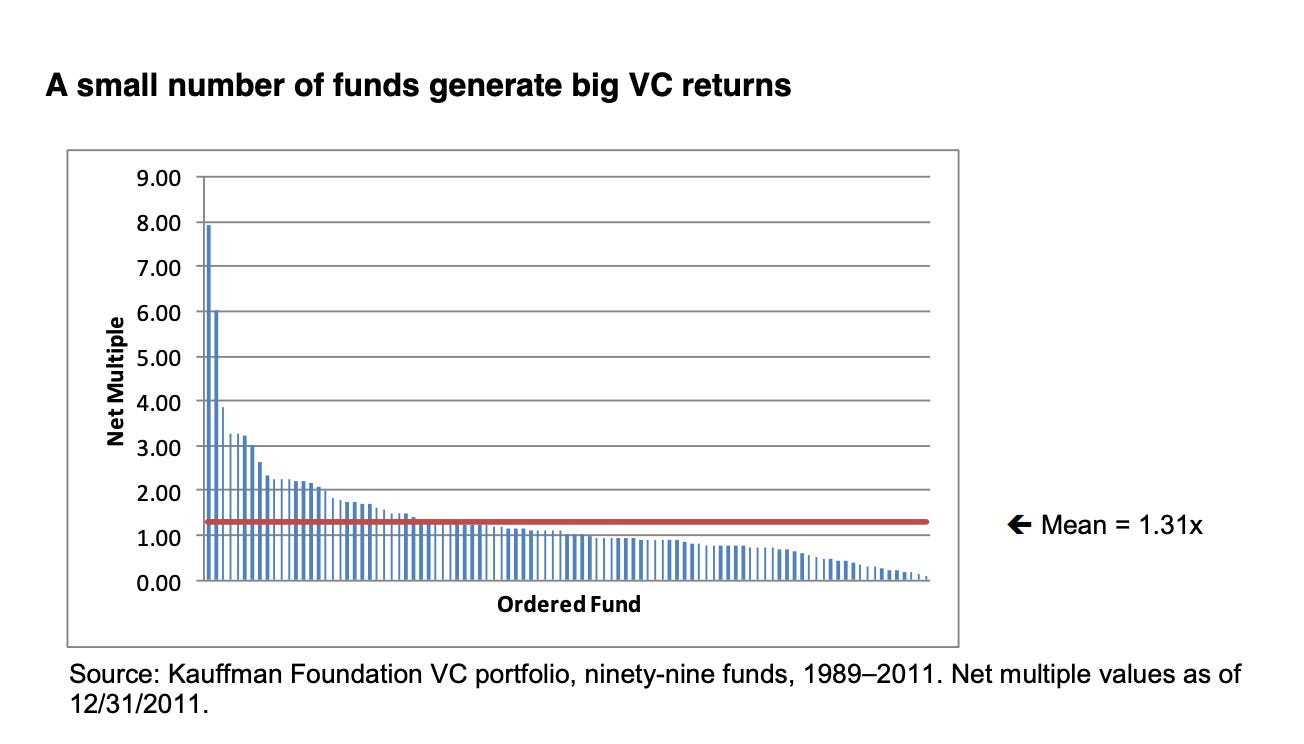

Most VC firms have portfolios of 15-25 companies per fund. Very concentrated, the exact opposite of the strategy I’m proposing.

This is despite the fact that the concentrated strategy is only working out for a small number of firms. Most of them barely even break even.

So why do VC’s have such small portfolios?

There is an argument that it’s a function of bandwidth - there isn’t time to review all the deals and write so many small cheques, handle governance, board seats, etc. There is obviously truth in this; if you want to take an active role in companies, you cannot spread yourself too thinly. But do you need to sit on all those boards? Do you need to do the level of analysis and diligence you are doing?

As Charlie Munger once said, “Show me the incentive, I'll show you the outcome.”

Venture firms charge hefty fees. The classic model is “2 and 20” - 2% in cash per annum (dropping off a bit as the fund matures), plus 20% of profits on exit.

If you’re charging such high cash fees in particular, you need to look like you’re doing something to justify all the money your investors are paying you. So you sit on boards, hire a team of analysts, build financial models and spend a ton of time assessing deals and debating at great length which ones to invest in and which ones to pass on.

For 5% - 10% of VC’s this seems to work. For everyone else, it doesn’t.

The other factor at play is ego - despite the fact that only 5 - 10% of investors are really performing, the majority think they’ve got an above average shot at being in the top decile.

So how do you build your index?

If you decide after reading this that you’re going to try the indexing approach, remember - you still need a quality filter. You shouldn’t just be investing at random, since the bottom 90% of startups will return nothing substantial.

If you’re a newbie, the chance you’ll end up indexing the bottom half is pretty high.

This is why investing smaller cheques via syndicates & funds with access to quality makes a lot of sense.

If you’re doing it yourself, you need to spend a lot of time honing your ability to identify great founders going after big market opportunities (much harder than it sounds) and then work very hard to get access to their funding rounds.

Finally, assuming you only get exposure to 10 or 15 deals a year, you also need to be willing to commit to investing in this asset class as a long-term endeavour.

And, finally, regardless of your strategy you must be prepared to suffer a lot along the way.

🤔 and 😂 stuff

Silver Linings

“Far from a disaster, Kwarteng’s plan could be transformative. It just needs to be delivered.”

An optimistic take from Keir Bradwell on Kwasi Kwarteng’s mini budget.

Dry powder ≠ more funding for startups

My boy’s wicked smaht

The same investment ideas you get in this newsletter, delivered in the form of a Good Will Hunting parody thread.

Jeflon Zuckergates

The release of Stable Diffusion and Midjourney as open source / highly accessible products hot on the tail of DallE-3 is leading to an explosion of fun content on Twitter.

Risk Warning

The above information is not investment advice and is for informational purposes only. Investing in start-ups and early stage businesses involves risks, including illiquidity, lack of dividends, loss of investment and dilution, and it should be done only as part of a diversified portfolio.

Join Odin Limited (trading as “Odin”) is registered in England (No.12849405), with registered office at Unit 105, 65 - 69 Shelton Street, London, WC2H 9HE.

Access to the Odin platform is restricted only to those individuals who are able to first truthfully evidence that they are persons eligible to receive exempted financial promotions in respect of private investment opportunities in compliance with the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (Financial Promotion) Order 2005 (SI 2005/1529).

Odin is not regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority.

Colin West - Venture returns with Abe Othman of AngelList

if there should be an article to discourage people in investing in startup or creating a startup should be this one

Show me the incentive, I'll show you the outcome.

You are trying to build an index on venture because you are trying to convince people to invest through your platform and disrupt traditional venture capital. So this story fits your agenda nicely.

What you failed to put into your math was variable power law formulas by stage. Later stage looks more logarithmic than does early stage. You also failed to include the concept of follow-on investing, which is how the majority of fund dry powder creates more certain returns - if those dollars are wasted on power law distributions, they'll fail to get the lower loss-rate (and lower MOIC) returns that help boost returns once the few winners are known.

Your company has a future in venture, but trying to do venture math is obviously not your strong suit.