Network Effects (part 1)

What they are, how they work, and where to look for them

Hi folks, Patrick Ryan here from Odin.

We build powerful tools for VC’s, angels and founders to raise and deploy capital seamlessly.

In 1913, John D. Rockefeller was the world’s wealthiest human being.

His net worth was an estimated $900 million. This was equivalent to almost 3% of US GDP that year.1 Today that would mean a net worth of around $600 billion (if similarly expressed as 3% of US GDP).

For context, Elon is worth $238B2 - well less than half of that.

Rockefeller was the founder of Standard Oil, a company that came to dominate the US oil industry. At its peak, in the early 1900’s, Standard controlled around 90% of oil refining and distribution in the United States.

At the heart of this dominance was an innovative business strategy. John D. Rockefeller leveraged a phenomenon we now commonly call a network effect.

What are Network Effects?

Simply put, network effects occur when the value of a product or service increases as more people use it.

An easy to understand example of this is a telephone network:

The more people are connected to the network, the more different conversations can happen.

The relationship is non-linear. So as the network gets bigger, it gets exponentially more valuable as an entity. It kind of becomes more valuable than the sum of its parts.

In the above example, the number of phones has increased only 6x, but the number of connections has increased 66x. By the time you have 1,000 phones, there are over 500,000 possible connections. So owning a phone is WAY more useful.

The larger a network like this gets, the less sense it makes to leave and join a competing one. Think about Twitter vs. the next most popular “microblogging” social network, Mastodon (if you’ve even heard of them).

As you can see, this makes controlling networks a very valuable business to be in.

Standard Oil’s Network Effect

Standard started out in the refining business. They bought crude oil and turned it into hydrocarbons for everything from fuel to plastics.

This was a competitive business. But Rockefeller recognised something interesting: all the other stakeholders in the ecosystem - other refineries, suppliers (oil wells), service providers (eg. storage facilities), and customers (eg. factories in big cities) - were connected to each other by the same vast network of railways and pipelines.

This network was vital to everyone’s ability to sell their products.

So he set out to dominate it.

Initially, Standard negotiated favourable rebates and exclusive deals with railroads and other transportation companies. By securing these agreements, they gradually made it more difficult for competitors to access suppliers and customers at competitive prices.

They then began to engage in more and more aggressive horizontal integration, by acquiring or establishing absolute control over numerous competing oil refineries, pipelines and transportation networks.

As the company expanded and increased their control over both “nodes” in the network (refineries), and the connections between them (railways, pipelines, etc.), it created a highly efficient system that was extremely difficult for competitors to replicate. They could refine oil faster because their refinery network was bigger, and they could deliver it faster and more cheaply to the customer because they dominated distribution.

This made it even more attractive for new suppliers and customers to work with Standard. This in turn further reinforced the company’s power, by giving them control over more nodes in the network.

As Standard continued to grow, they also integrated vertically, acquiring or establishing control over upstream and downstream industries such as oil exploration, drilling operations, and storage. This allowed them to achieve economies of scale, and additional network control. By this point, they were able to significantly undercut competitors on price and drive their businesses into the ground.

As a result, eventually, they dominated basically the entire supply chain and distribution network for oil in the USA, from the extraction of crude oil to the delivery of refined products.

This, in turn, led to unheard of profits.

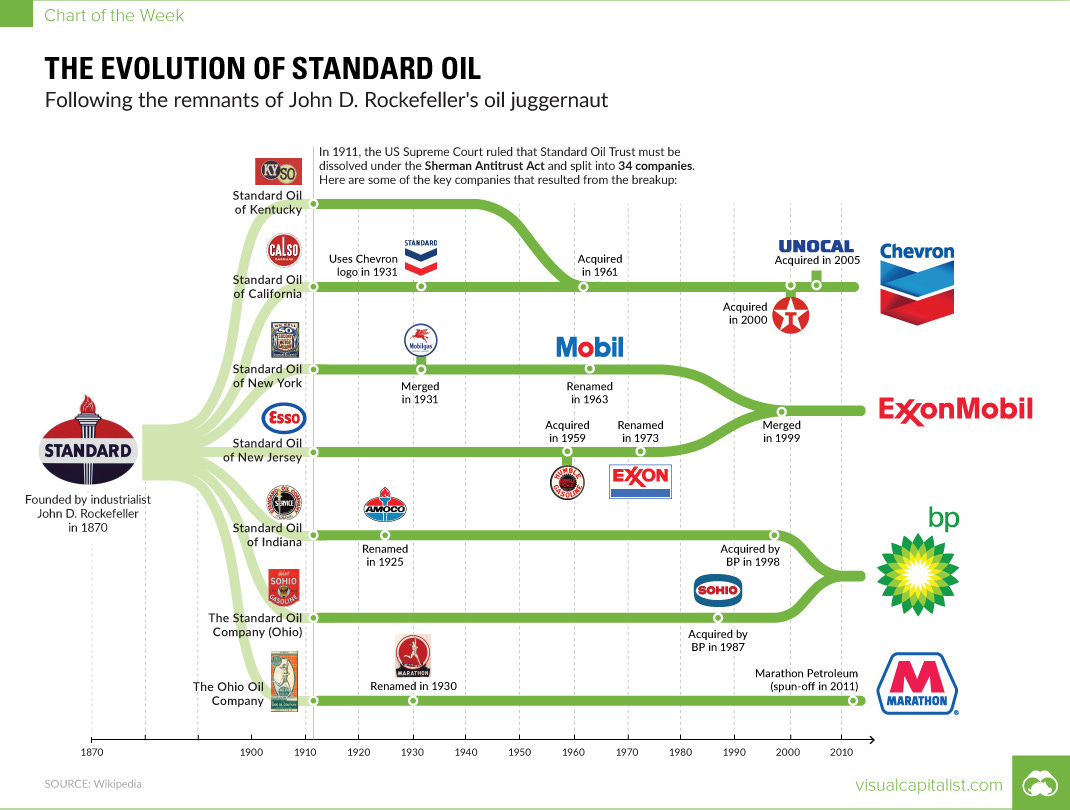

Standard’s position was so powerful that it was eventually broken up under antitrust laws in 1911. These laws were created as a direct result of the rise of Rockefeller’s monopoly (as well as others like it).3

The company has multiple powerful successors. The most famous is known as ExxonMobil, the largest investor-owned oil company in the world. Many other companies are either direct descendants of Standard Oil (such as Chevron and Marathon Oil) or have acquired a Standard Oil descendant (such as BP and Unilever).

The Modern Economy is built on Network Effects

The internet is the modern day equivalent of the oil pipelines and railway networks that Rockefeller sought to dominate.

Instead of transporting oil, it transports information.

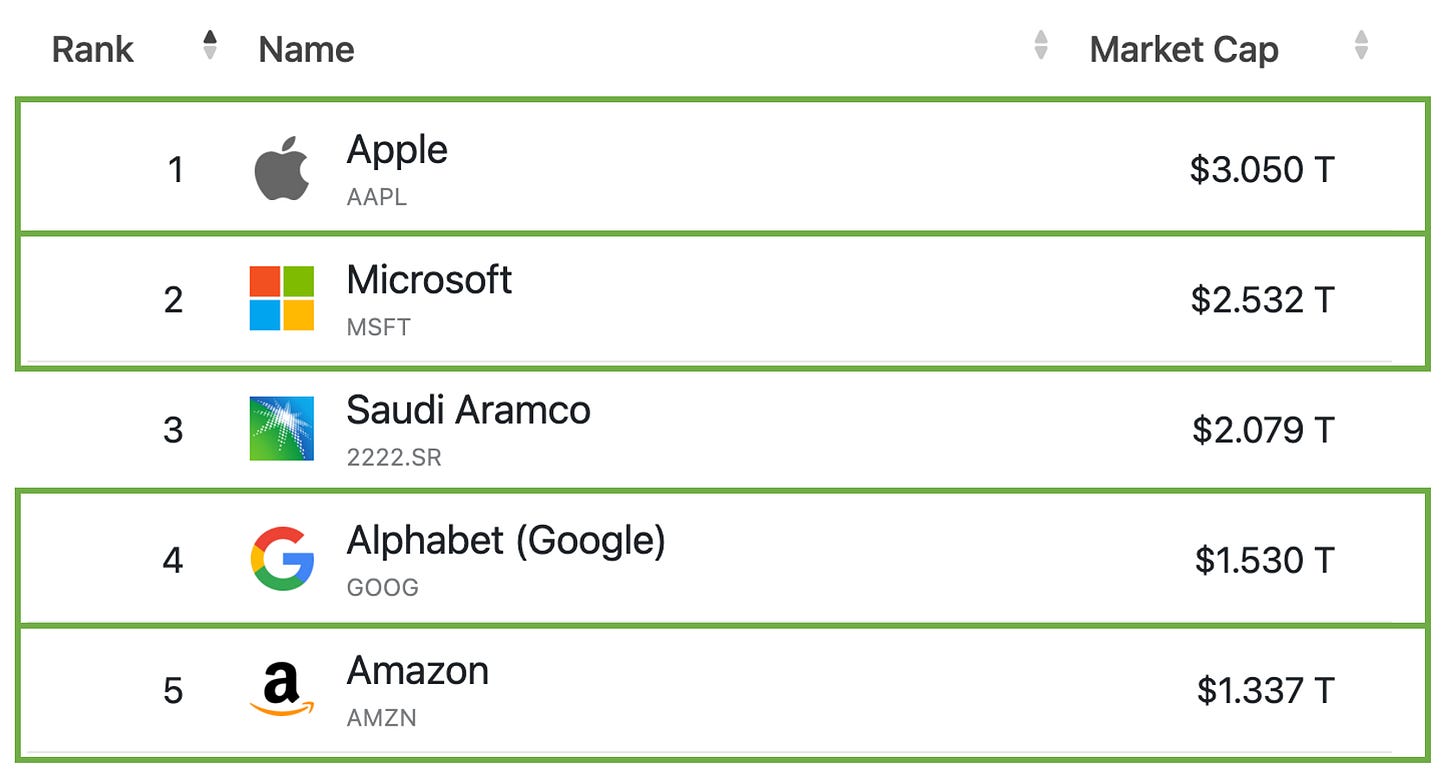

Of the 5 most valuable companies in the world today, 4 benefit directly from a network effect. In some way, they’re leveraging the connection between their users, suppliers and partners to build a quasi-monopoly in their corner of the global information superhighway.

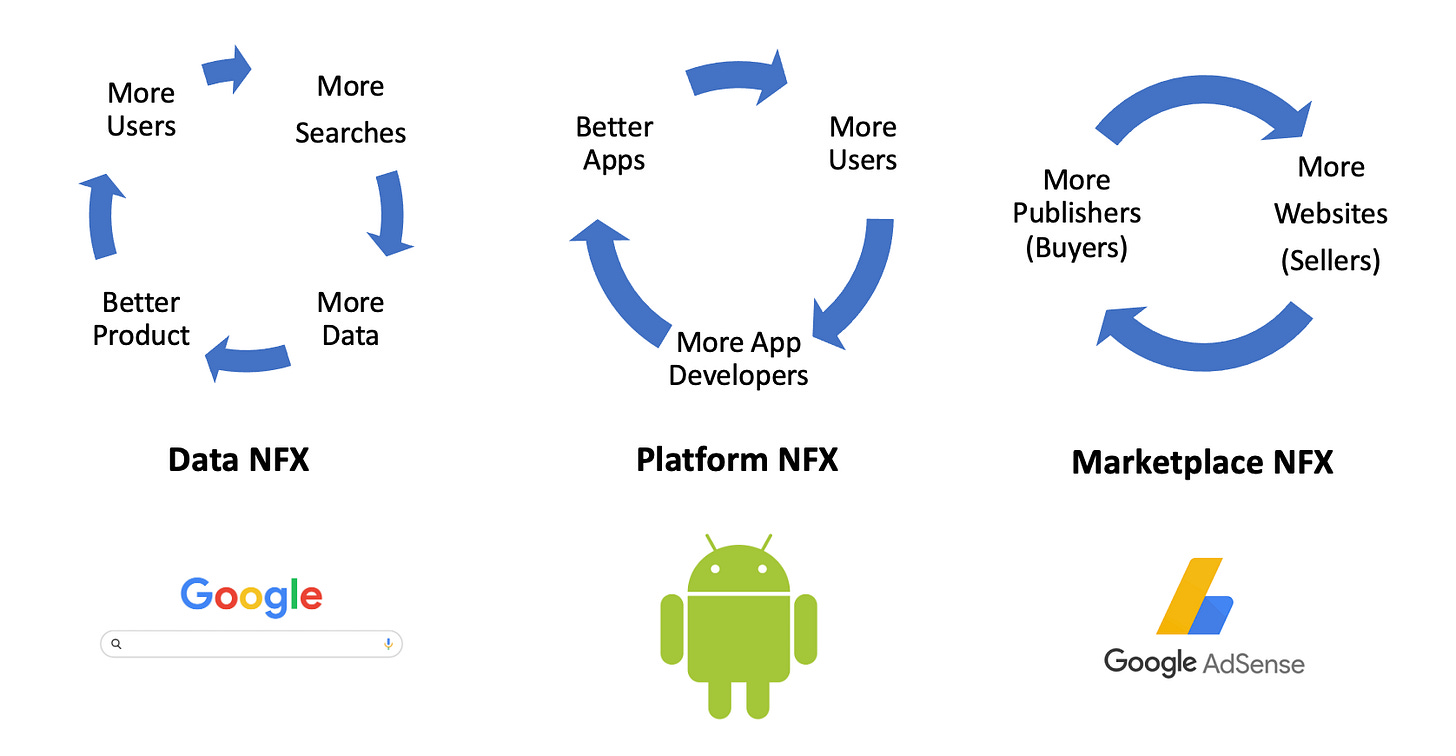

Take the example of Alphabet / Google. It benefits from data network effects in its search product, marketplace network effects in its advertising network, AdSense, and platform network effects in its Android operating system:

Microsoft (Windows) and Apple (IoS / Mac OS) also benefit from platform network effects.

They start out by acquiring a critical mass of users to their platform. This attracts developers, who build apps to sell to their users.

Having access to lots of good apps attracts more users.Eventually, people don’t really build apps for anything else.

This means these platforms have incredible market control once they scale. Apple charges app developers 30% of their revenue in “rent” to be on their platform. People complain, but do they stop making apps for the iPhone? Of course not.

Remember that crazy video of Steve Ballmer screaming “developers, developers, developers”?

Now you know why he likes them.

Thanks for reading!

In part two, we will look at startup investing through the lens of network effects, explore the different types of network effect that exist in more detail, and assess how this affects the prospective value and defensibility of a startup.

If you’re looking to syndicate an investment in a company with network effects, check out Odin.

PR

You got me there. Never heard of Mastodon. I thought I was hip for knowing about Substack.