The Reserves Paradox

The Emerging Manager's Guide to Reserves in Venture Capital

The Odin Times is brought to you by Odin.

We let anyone, anywhere launch and run a private investment firm online, and work with over 10,000 VCs, angels and founders globally.

Good morning!

Please give a warm welcome to Dan Gray, who joins Odin as Research Lead!

Dan has spent years deep in the weeds of academic literature on venture capital & private equity, and we share a passion for and belief in the massive economic value that emerging fund managers can bring to society, especially radical managers with radical ideas about how the world could look very different. You can follow Dan on Twitter and LinkedIn - well worth it!

This is the first post in a new series of guides we are producing for emerging fund managers, covering everything from sourcing through to fund structuring. Today we’ll dive into the thorny topic of reserves. Let’s get going.

“In the beginning the majority of our fund was for initial investments, and now the majority of our fund is some level of reserve for follow-on. I don’t know if we’re good at it. I could say to a founder right now that I think there are few firms as good as First Round to be your partner for the first 24-36 months. The hunt for massive product:market fit, building culture, building a team, figuring out pricing and positioning… all that stuff, that’s our power alley. I don’t know if we would be the best partner for founders at the later stage, and maybe we’re just a dumb provider of capital.”

- Josh Kopelman, Founder of First Round

Are Reserves a Good Use of Capital?

In simple terms, a “reserves strategy” represents the capital that a firm will hold back in a fund to make follow-on investments in the future rounds of portfolio companies.

In the common wisdom of venture capital, there are two competing narratives about the use of reserves:

Reserves are a crucial way to improve performance by doubling down on your winners. They offer an opportunity to build or preserve ownership in the best companies, generating more alpha from asymmetric insider knowledge.

Reserves are a scam. Subsequent rounds are typically a significant step-up in price without a meaningful change in the risk profile of the company. Good piece from James Heath on this in October last year.

This is further confused by the fact that analysis seems to suggest that reserve strategies rarely make sense, and yet remain common practice.

“While reserves can occasionally boost returns, they can, and more frequently do, bring down fund multiples. They also (dare I say) sometimes create potential conflicts of interest with LPs. This is why LPs want to understand how a GP thinks about using reserves.”

So, how should an emerging manager think about reserves in the present and future of their firm? We’ll run through all of the considerations.

A Magnifier of Performance

Reserves function as a form of concentration, which is the opposing force to diversification:

Concentration = owning a larger % of a smaller pool of companies, so more upside is captured in the event of an exit.

Diversification = owning a smaller % of a larger pool of companies, so your portfolio is (a) more tolerant of failure and (b) statistically more likely to hit outliers.

Balancing these forces is a fundamental question for any investment strategy, and all elements (fund size, target stage, typical round size, failure rate, future dilution) play a part in informing the correct approach to risk and reward.

Research helps to illustrate the general trade-off for investors here:

“Increasing concentration has a pronounced positive impact on performance for outperforming funds; the opposite is true for underperforming funds. Most importantly, higher levels of concentration generally hurt the poorly performing funds more than it helps the outperforming funds.”

Essentially, if you believe you can reliably predict good and bad investments in your portfolio based on a few years of observation, reserves can help compound those good decisions, by increasing your concentration in your winners. However, most of the time it’s likely to add unwelcome risk.

Implicitly, this means reserves become more obviously beneficial for later stage investing, where failure rates are generally lower and companies produce more metrics that are more predictive of trajectory. Older firms with a longer track record (and better internal processes to track investments) also have an easier time getting value out of reserves.

For emerging managers who are typically investing in the earliest stages, it’s important to recognise the trade-offs in a dedicated reserves strategy. It should not be treated as the default approach.

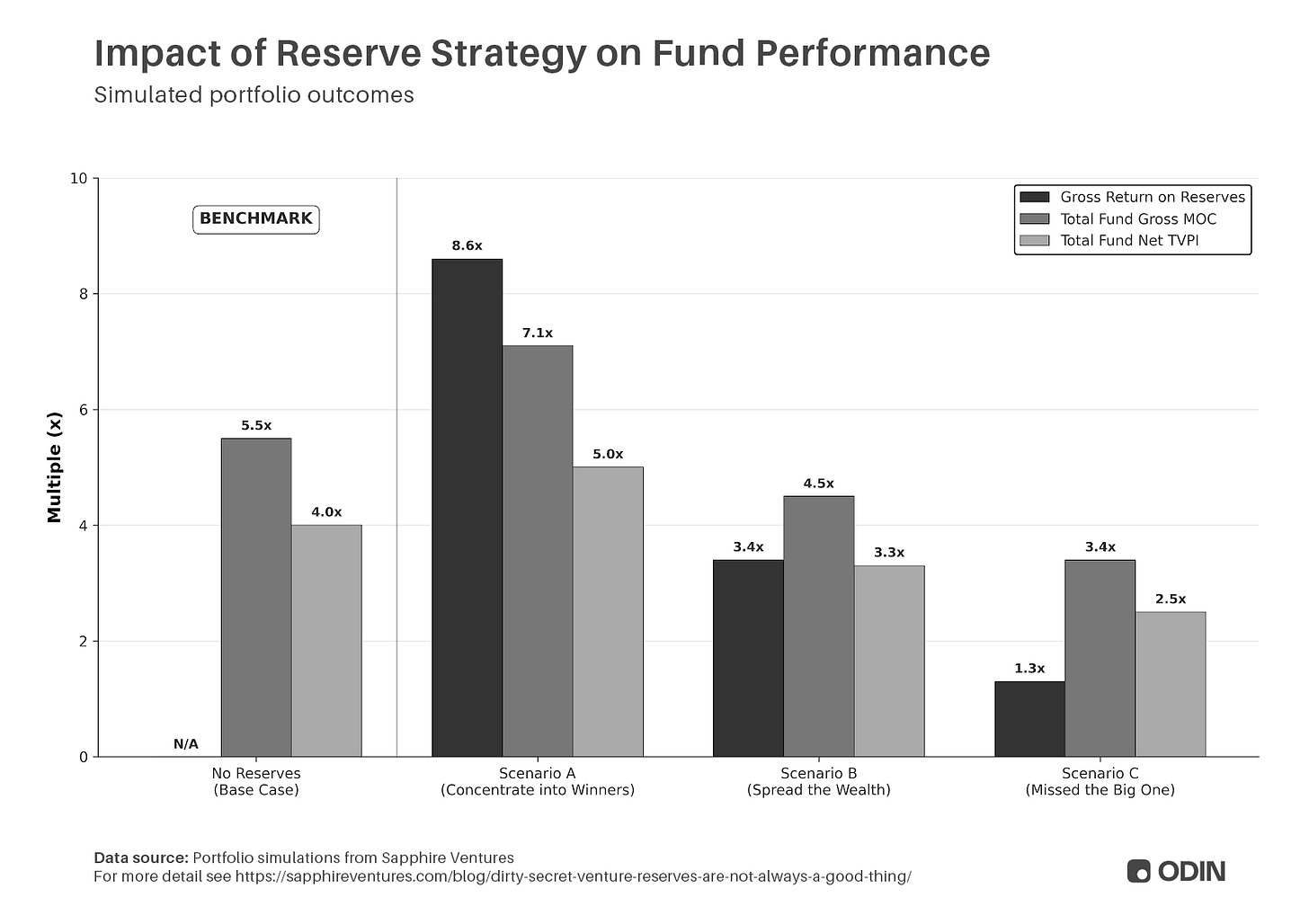

To break this down, we can take a closer look at the simulated portfolio data from Sapphire Ventures, illustrating how difficult it is improve fund performance by adding reserves:

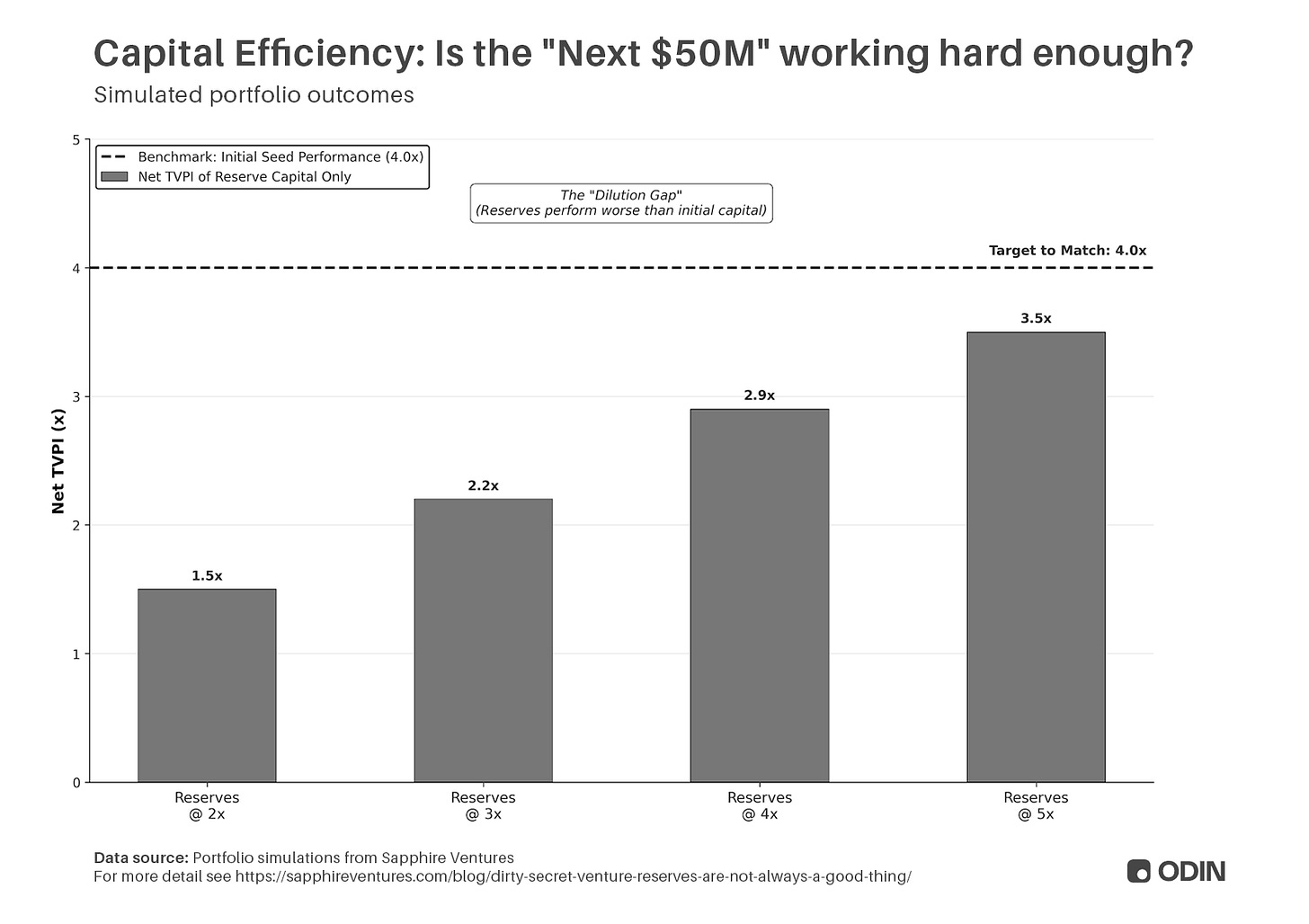

Reserves @ 2x: If the follow-on capital only generates a 2x Gross return, its contribution to the fund is a sad 1.5x Net TVPI. This is “dead weight” that drags the total fund performance down from 4.0x to 2.7x. The GP has effectively diluted their own track record by raising more money than they could efficiently deploy.

Reserves @ 3x - 4x: Even with solid outcomes where reserves triple or quadruple in value, the marginal efficiency (2.2x – 2.9x Net) remains well below the 4.0x benchmark. The fund is getting bigger, but its performance metrics are getting worse.

Reserves @ 5x: Even if the GP executes brilliantly, and generates a 5x Gross Return on follow-ons, the net impact of that capital is only 3.5x Net TVPI. Because this is still lower than the 4.0x seed benchmark, even this “home run” scenario lowers the fund’s overall average.

As an inexperienced manager investing at the most unpredictable stage, are you willing to bet that you’re going to pick ~25 amazing companies right off the bat, and follow on into all the right ones? Or would you rather double your probability of finding the next generational outcomes like Spotify, Revolut or Elevenlabs?

The Cost of Reserves

Another basic consideration for reserves is simply whether a GP can raise enough capital to cover follow-on activity. A common rule-of-thumb is a 1:1 ratio of initial capital to reserves, implying doubling fund size, which further rules out many capital-constrained emerging managers.

The value you can extract from a reserves strategy is directly dependent on the quality of your initial investments. The more initial investments you can make, the more likely you are to find great companies. This is the tension of reserves: the utility relies on your ability to find great companies, which is easier with a larger portfolio. However setting aside capital for reserves implies a smaller portfolio.

Indeed, underdiversification is already an area of concern for early-stage venture capital, making it difficult to justify fund expansion that amplifies risk further.

“This model seems to show that the larger your portfolio, the better you’re likely to do. Why should that be so? With a power law distribution of returns, success is all about hitting that rare outlier. Other things being equal, the more chances you have, the greater the chance of a big hit.”

- Steve Crossan, Founder of Dayhoff Labs, venture/operating partner at multiple funds

An important additional caveat: generally speaking (unless you are very careful about maintaining the same pool of LPs) you will not be able to use a later fund to invest in later rounds of a particular portfolio company. LPs will not want to provide financial support to an investment where they only capture a fraction of the upside.

Emerging fund manager looking for a people-centric digital back office partner who understands your business? Speak to our team

The conclusion appears to be that reserves are not likely to be a good strategy for new managers. However, that doesn’t mean it’s not worth thinking about for the future.

Is your long-term goal to build a collaborative Seed-focused firm that would benefit from greater diversification and the commensurate network effects (e.g. First Round with ~70 companies per fund, or Boost VC with >100 companies per fund)?

Or, are you building a traditional early-stage firm that aims for greater concentration and a more active role in fewer portfolio companies (e.g. Lowercase capital with 10-15 companies per fund, or Hummingbird VC with <20 companies per fund)?

This question will help decide if reserves should become a priority later on.

Alongside this fundamental question, reserves have a number of second-order consequences which are important to consider:

Signalling

Portfolio support

Incentive alignment

Sunk-cost fallacy

Let’s run through them.

Important Considerations for a Reserves Strategy

Signalling

One of the ‘soft sciences’ of venture capital, signalling refers to how the activity of an investor might inform the decision of other investors looking at the same company.

For example, if a large multi-stage firm leads the Seed round of a startup, but then doesn’t participate in the Series A, this is interpreted as a negative signal. Their decision not to invest is seen as a consequence of having insider information.

“If a VC invests in your seed round and does not participate in a future round the next round investor will think to himself, “well, if Big VC Co. invested in the seed round they have more inside knowledge than I do. If they’re not willing to fund the next round then something must be wrong with this company.” This is true and does happen.”

This may in turn make the life of that company even more difficult, further ensuring a negative outcome. For some VCs this is a good enough reason to avoid a formal reserves policy, and the related signalling risk.

However, the signal strength of a VC firm develops over time, alongside their reputation, so the associated risk is actually minimal for emerging managers. The market isn’t likely to read much into a missed follow-on opportunity.

Later on, the risk is eliminated entirely if you hardly ever do follow-ons, or if (like USV) you never pass on a follow-on opportunity. In these cases there is no real signal to the market about your belief in other portfolio companies.

“Our pass rate is zero. Never happened. Not once in the history of USV. In many cases, we should have, but we did not. We have passed on late stage rounds where our participation was not required and the round was oversubscribed, but when our participation has been necessary, we have always done it.”

Support

Startups are virtually never straightforward success stories. Many of the best companies had struggles with fundraising early in their lives, and will have benefitted from their initial investors having capital to support them through later rounds.

“There is surprisingly little correlation between how hot a company is at Demo Day and how well they end up doing. Coinbase struggled to raise money after YC but ended up doing the best in their batch.”

While a diversified Seed fund may not worry about filling this supporting role, it’s likely that another firm with a more concentrated strategy might. This becomes particularly important in periods of market turbulence, where other sources of funding may dry up.

The implication here is that a comprehensive reserves strategy is not simply for backing “obvious winners” with momentum, but for doubling-down on your own conviction, especially when the going gets tough. The more trouble a company has, the lower their subsequent valuation, the more important protecting yourself from dilution may become.

Incentive Misalignment

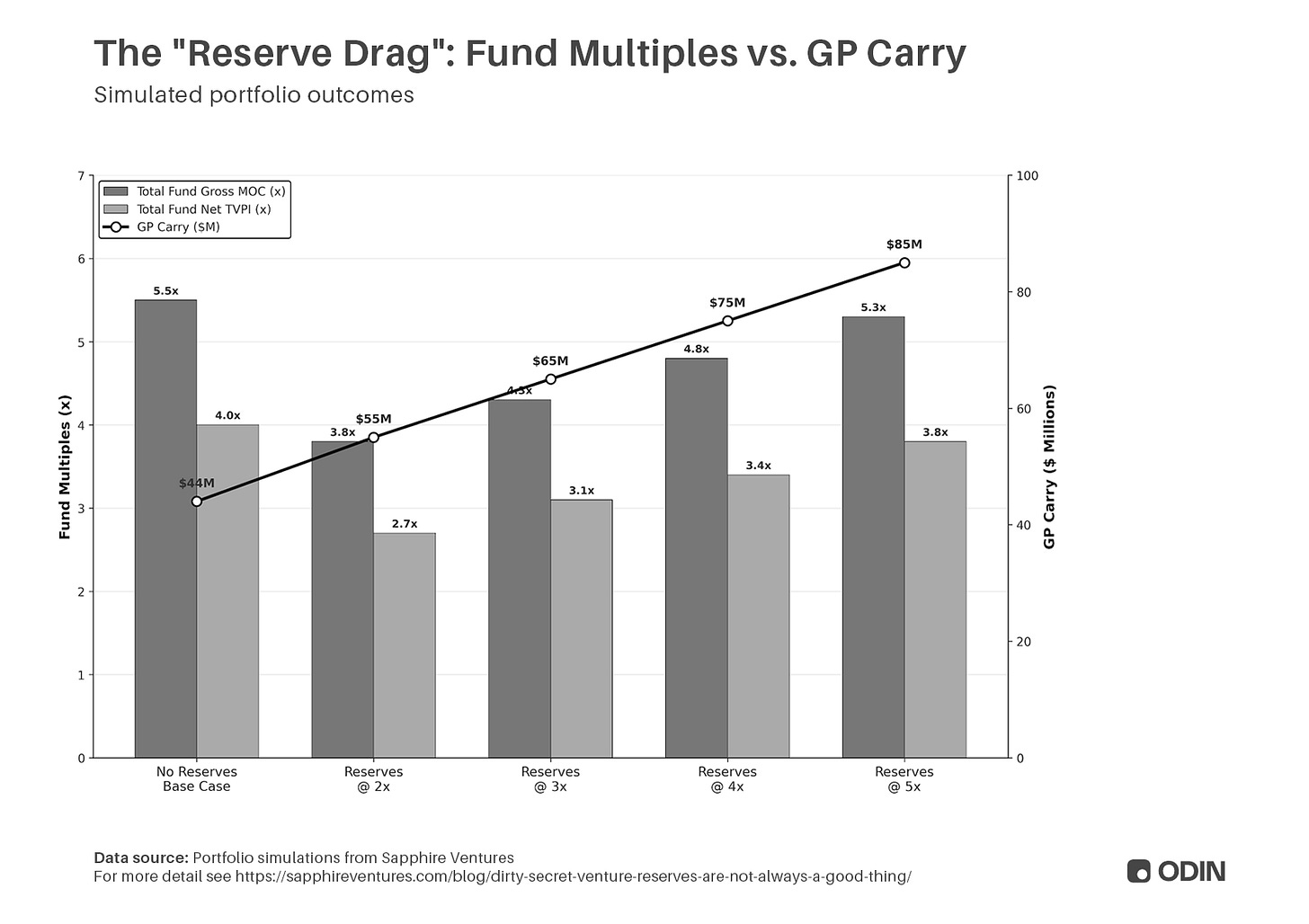

Efficient returns are best achieved by smaller funds. GPs, however, are incentivised to prioritise their management fee income, which means raising larger funds. Thus bolting on a reserves strategy often benefits the manager more than the LP, as the additional capital acts as a drag on the overall portfolio performance.

Again, this is well-illustrated in the simulated data from Sapphire Ventures:

In the “Reserves @ 2x” scenario, the fund’s Net TVPI falls from a solid 4.0x to a mediocre 2.7x. Paradoxically, the GP’s carry increases by $11M, rewarding them for managing a larger, less efficient fund.

Even in the best-case “Reserves @ 5x” scenario, the fund’s net multiple (3.8x) fails to recover to the original “No Reserves” benchmark (4.0x), proving how difficult it is to maintain efficiency at scale.

While dedicated reserves remain fairly common, it’s worth keeping in mind that LPs are increasingly wary. Are you raising more capital as part of a carefully considered strategy, or is it an excuse to pad out your fund?

Sunk-cost Fallacy

There’s an obvious danger of “sunk-cost fallacy” playing a role in the execution of a reserve strategy. While investors should try and be as laser-focused as they can on objective metrics and personal conviction, it can be hard to overcome biases like market momentum and relationships.

Research tells us that the more time a VC has spent with a particular portfolio company, the more likely they are to invest in follow-on rounds. Similarly, the more capital they have contributed to previous rounds, the more likely they are to participate in future.

“Based on a dataset of 30,602 investment decisions about US-based portfolio companies from 2009 to 2019, we find that both the amount of capital previously invested and the intensity of monitoring significantly increase the probability of continued investment, underscoring the sunk cost fallacy’s role in venture capital.”

It is therefore important, where the follow-on process is selective, that each new round of a portfolio company be considered independent of any prior financing or existing relationship.

The Barbell of Reserve Allocation

“The Seed Fund” - Informal follow-on

For firms focused on the earliest stages, and especially emerging managers, a defined reserves strategy doesn’t make sense for the reasons outlined above. However, that doesn’t necessarily mean you cannot participate.

In rare instances where you have extremely high conviction and believe it’s worth making an exception (e.g. for helping get a round over the line) you can usually get a little wiggle room with your LPs for investments outside of the usual scope. This may just be LPs allowing you the latitude, or sometimes GPs might build an ‘out of thesis’ allocation (10-20%) into their LPA, allowing for investments beyond the main stage, industry and market targets.

While it can be tempting (particularly under the threat of signalling risks) to simply never do follow-ons, it’s unwise to tie your own hands in an industry that is built on exceptions. Especially when it may help shape your learning for a more sophisticated strategy later on.

“The Legacy Firm” - Always follow-on

For more established firms, with a track-record of good judgement which allows for larger fund sizes, the best model to consider might be that of USV. Acknowledging that it’s impossible to know who your winning investments are early on, and that renowned VC firms carry more signal, they simply choose to back all of their portfolio companies to the bitter end (and it seems to work for them).

For as long as their initial investments are well judged, this strategy is likely to help firms graduate from solid-performers (~4-5x) into all-time greats (>7x). However, in a world where only 6% of venture funds are delivering more than 5x returns, managers should be honest about whether the additional risk is worthwhile.

Other Ways to Follow-On

While reserves are the primary vehicle for follow-on capital, there are a few other approaches which may be attractive.

SPV Capital

Firstly, there’s the approach used by many small firms such as Everywhere Ventures, RareBreed Ventures and Hustle Fund, where the fund exists for initial investments, and follow-on allocation is opened up via an SPV. This allows a venture firm to support their portfolio companies with follow-on capital without putting their fund performance at any direct risk. It also gives more active LPs the opportunity to get more direct exposure to companies that they particularly like.

This is going to make the most sense for Family Offices and HNWIs who may value the deal flow. It will tend to be hit-or-miss for a Fund of Funds (for some co-investments of this nature are actually a dedicated part of their strategy), and be unappealing to larger institutions who usually don’t want the admin burden. This aligns well with the typical LP-base of an emerging manager.

Opportunity Funds

Secondly, there’s the strategy usually employed by larger firms, which is to raise specific “opportunity funds” which allow for concentration in their later-stage winners. These funds may be “stapled” to their early-stage funds (so an LP in one must also invest in the other) in order to ensure LP continuity. This allows for meaningful participation in larger, late-stage rounds.

The capital requirements of this strategy also lean towards the larger institutional LPs which tend to back these larger firms, making this a distant consideration for most emerging managers.

Conclusion: Start Small and Experiment

The most common question from emerging managers is “How much should I allocate to reserves?”, and the best answer is probably “As much as you believe you can make a good return on.”

The value of reserves is so dependent on when, where and how you invest. This makes it impossible to outline a generic set of best practices. Certainly, there should be no assumption of reserves as a default strategy.

Fortunately, you can run limited experiments, like an entrepreneur. In your first fund, you might never make a follow-on investment if the right opportunity doesn’t appear, or you might make a handful (capital/LP flexibility allowing). Carefully monitor the outcome of those decisions, and consider the opportunity cost of any allocated capital.

If those experiments seem to pay off, you might want to consider a formal allocation for follow-ons in your next fund. Expand the experiment, get more data. You may eventually end up with >50% of the fund in reserves, like First Round Capital. However, as Josh Kopelman implies, you might never really be certain it’s the best use of that capital. The only way to tell is to carefully track performance over time.

I definitely recommend follow-on via SPV rather than the originating fund. And if you really want to be a good fiduciary to your LPs, you might consider pushing your SPV carry back into the originating fund (or at least some of it).

Another strategy which may make sense if your initial check size is at least $500K-$1M is to make your initial investment via SPV from the very beginning (where your fund is 100% of the SPV capital). Then you can use the SPV both to follow-on in subsequent rounds, as well as perhaps transfer some of the fund ownership to other SPV LPs (or even your own continuity vehicle) in order to generate liquidity / DPI for the fund. Obviously there are some tradeoffs here for TVPI vs DPI, however you can more efficiently manage liquidity within the SPV by keeping the same entity on the cap table.

Really insightful breakdown. The part where even 5x reserve returns get dragged below 4x seed benchmark flipped my whole understanding of fund scaling. Been on an LP board where we kept pushing for bigger funds, and now I see we might've been incentivising carry over performnce. That sunk-cost research around monitoring intensity is kinda validating.