Network Effects (part 2)

The reason network effects are the single biggest predictor of outlier returns in VC, the different types of nfx company that exist, and a framework for assessing their prospective exit value

Hi folks, Patrick Ryan here from Odin.

We build powerful tools for VC’s and angels to raise and deploy capital seamlessly.

We take care of legals, fund admin, payments & banking, so you can focus on investing. Founders can also use Odin to raise capital from their network in a few clicks.

Today we are going to dig deeper on the subject of network effects.

We’ll cover:

A bit of history - How the Bell Company’s telephone network led indirectly to the creation of Silicon Valley;

Why the internet strongly favours business models with network effects, and why nfx are probably the biggest predictor of outlier returns in venture capital;

The different types of network effect that exist in modern software companies;

Why not all network effects are equal, and how this affects the prospective value and defensibility of a startup.

If you have a decent knowledge of the history and how NFX work, feel free to skip straight to the final section: “Types of Network Effect and why they’re not all equal”. I think you’ll hopefully still discover some new ideas there.

I want to say a special thank you to Sameer Singh - I’ve leaned heavily on his research in the latter half of the piece. Sameer is a venture partner at Speedinvest, and also invests, primarily at pre-seed and seed, as part of the Atomico angel program. He only invests in companies that exhibit network effects.

Sameer and I recorded a conversation a few weeks back - so if you prefer listening to reading, check it out!

And if you’re looking for Network Effects (Part 1), here it is. It’s a short primer on the subject. Today we will go into more detail.

How Alexander Graham Bell built the modern world (kind of)

As many of you hopefully remember, network effects occur when the value of a product or service increases the more it is used.

My favourite example is a telephone network:

The more people are connected to the network, the more different conversations can happen.

The relationship is non-linear. As the network gets bigger, it gets exponentially more valuable as an entity. This is known as Metcalfe’s Law.

Because of Metcalfe’s Law, that which is ahead has a tendency to get further ahead. Business models with network effects therefore have a tendency towards monopoly.

Let’s say you own a phone network with a million phones connected to it, and someone else starts a new network, initially with 100 phones (maybe their friends and family join). Which one are the general public going to want to join? It’s pretty obvious.

A monopoly is exactly what the Bell Company, the USA’s first telephone network, became. The company was founded in 1877 by Alexander Graham Bell and his father-in-law, following Bell’s invention of the telephone.

In the period up to 1900, the Bell Company grew incredibly fast, and aggressively bought up smaller competitors that had succeeded in dominating specific regions of the USA. In 1885 they established a subsidiary called the American Telephone and Telegraph Company (AT&T) to build and operate a long-distance network. Up until that point, most phone networks were local only. AT&T were the first company to connect people across the United States.

Thus began the monopolistic period of “Ma Bell”.

In a strategic move, AT&T was restructured as the parent company of the Bell System in 1899. Throughout the 20th century, AT&T grew in power. It eventually controlled the majority of the nation's phone service and much of its communications infrastructure.

Interestingly, unlike many other companies that were broken up under Antitrust, the government effectively sanctioned AT&T's monopoly status. As long as it operated in the public's interest, by allowing non-competing independent telephone companies to interconnect with its network (as you can imagine, there weren’t many), it was allowed to continue to dominate.1

Now, as you’ll know, owning a monopoly generates a lot of free cash flow.

To paraphrase the Black Eyed Peas, what you gon’ do with all that cash?

Apple, a 21st century network effects monopoly, spends a lot of it on share buybacks, which has made Warren Buffet a very happy man.2

AT&T did something different though:

They invested heavily in R&D, through a subsidiary you may have heard of, called Bell Labs.

Bell Labs was AT&T’s moonshot skunkworks.

They hired the best scientists in the USA, and let them play. It became the birthplace of many of the 20th century’s key technological innovations - the solar cell, the satellite, the Unix operating system (which is the foundation that all of Apple’s OS is built on, interestingly) and the C programming language, to name a few.

However, there is one invention, above all others, that makes Bell Labs particularly special: the transistor.

This tiny electronic switch is the fundamental building block of modern electronic devices. A microchip is basically a circuit board of millions or even billions of tiny silicon transistors.

The first transistor was created at Bell Labs in 1947 by John Bardeen, Walter Brattain, and William Shockley. Shortly after the invention, Shockley moved to Mountain View, California and established Shockley Semiconductor, the first company in the region to work on silicon-based transistor technology.

We don’t have time to cover the fascinating evolution of this industry but in short Shockley planted a seed in California that grew into a very big tree, and eventually a forest.

He hired a number of very talented people, but he wasn’t a great manager (apparently he was an arsehole). His team felt that they were being short-changed in terms of equity and salary, so a number of them (the “Traitorous Eight”) left and started a new company called Fairchild Semiconductor.

Out of Fairchild, indirectly and directly, came countless semiconductor companies, including Intel and AMD (as well as Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers, one of the first VC firms in the Valley).

The proliferation of semiconductor companies, who initially built technology primarily for industrial and government applications, led eventually to the personal computer and, in turn, to the worldwide web - a networked system of computers not unlike Bell’s original telephone network.

The rest, as they say, is history.3

Why the Internet age favours network effects

The internet is a gigantic open access network for computers. Anyone can connect a device, and anyone can build software for any device that is connected. Because computers can do such a wide range of complex tasks, connecting lots of them to each other has democratised company creation, and made business much more competitive.

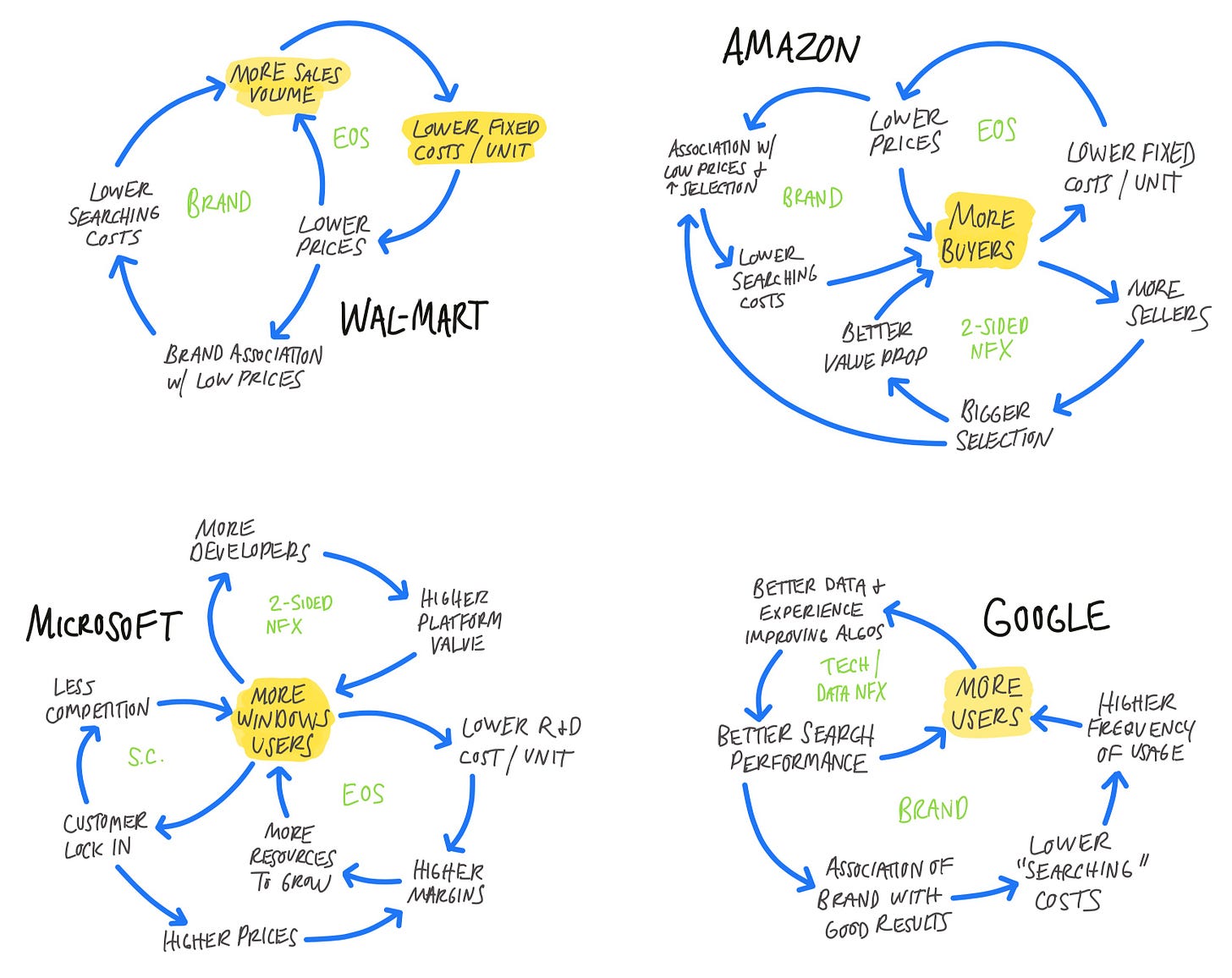

James Currier, founding partner at NFX capital, a network effects focused VC, argues4 that for software companies, there are only really four types of defensibility left in the internet age:

Scale - being bigger & using that to be ubiquitous and sell stuff cheaper;

Embedding - becoming very difficult to remove because you’re a key part of numerous processes & workflows in an organisation. Enterprise SaaS companies do this a lot.

Brand - brands remain incredibly powerful. People get into the habit of using something they know and trust, or develop an emotional connection with a business. This is very sticky behaviour.

Network Effects

Network effects are, probably, the biggest moat of the four.

If you look at the most valuable technology products in the world, what they are generally doing is carving out a corner of the internet dedicated to a specific service and building a walled garden on top of it that leverages a network effect to create a monopoly. They may also use embedding, and brand & scale come with the territory as you grow, but network effects are what really make the tech industry hum.

This is the playbook for Apple, Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp, X (Twitter), Google Search, Snapchat, Alibaba, Dropbox, Uber, Pinterest, Android, PayPal, LinkedIn, Deliveroo, Amazon, Slack, Zoom, TikTok, Pinduoduo, Instacart, Spotify, YouTube, Cash App, Tinder, Airbnb, OpenAI and more. Even B2B companies that you might not think of in this way - Microsoft, Shopify, Salesforce, HubSpot, Xero, Quickbooks - are leveraging network effects to monopolise their niche.

As more people use their product, or build apps for their platform, they create more connections, generate more data and/or offer access to more products, so it becomes increasingly useful to the existing user base - just like Bell’s telephone network5

However, because everything is built with software, the feedback loop is incredibly fast. It is much faster than the speed at which the Bell Company, which had to lay expensive and labour-intensive physical cables, could grow their network. Software, by comparison, is basically free to replicate and can be built by very small groups of people. Making changes to the software based on user feedback is quicker too.

This creates a powerful “flywheel”, meaning:

a) they grow even faster

b) the increased utility creates an ever-deeper a moat that quickly makes it harder and harder for other companies to do the same thing

What’s more, the proliferation of social products (Facebook, WhatsApp, Twitter, LinkedIn, etc.) means that new software has the potential to be shared with and adopted by millions of people rapidly. Social products want engagement, so they promote whatever is likely to drive the most engagement.

This leads to virality by design. Virality allows an idea to spread across our global networks at lightning speed. This in and of itself is not a network effect - it’s just word of mouth on steroids - but it means that businesses with network effects can acquire new customers very quickly, by piggybacking other businesses with network effects. It took Facebook, Twitter and Instagram years to reach 1m users. It took ChatGPT - piggybacking off platforms like Facebook, Twitter and Instagram - just 5 days.

As a result, software companies with network effects can get very big and very dominant very, very fast.

This has important implications if you’re thinking about investing in startups. It turns out that having a network effect has, for the last 30 years or so, been the single biggest predictor of outlier outcomes in venture capital (other than perhaps “great founders.”)

According to research from NFX capital, only 20% of tech startups actually have network effects, but if you look at the total value creation in tech over the last ~25 years, 70% of it is from companies with network effects.

Types of Network Effect and why they’re not all equal

Given the facts outlined above, I think it is worth having a pretty firm understanding of the details when it comes to this subject. You need to be able to look at a company and quickly ascertain:

What type of network effect it has (if any - in particular, a lot of people mistake virality (i.e. growth by word of mouth / referrals) for a network effect. They are not the same thing);

How strong and valuable that network effect will be over the long term.

Understanding this is useful whether you’re looking at a startup or a publicly listed company.

For (1), different people use different categorisation frameworks. NFX Capital list 16 different types.6 I find this a bit granular, and prefer Sameer’s framework, which lists four: marketplaces, interaction networks, data networks and platforms.

We’ll go through each one below and look at some examples.

You will notice that Sameer has placed all the relevant companies in an infographic with two axes: typically a Y axis for “supply differentiation” and an X axis for “geographic scale”.

Those in the top right quadrant are always more capital efficient, and tend to drive better ROI for investors.

This sounds quite abstract, but you’ll soon understand what I mean.

1. Marketplaces (eg. Uber, Airbnb, Amazon)

Airbnb is, in many ways, a perfect marketplace. Uber is not.

There are two reasons for this:

Airbnb’s supply is highly differentiated. Uber’s isn’t.

Marketplaces always require you to aggregate a fragmented supply and make it discoverable to the demand side. But aggregating a fragmented supply of something very similar and highly commoditised (like taxis) is less useful than aggregating a supply of something where people want to choose very specific items (like a “hipster apartment in New York” or a “log cabin in rural France”).Each user Airbnb acquires makes them more useful to other users globally. Uber’s utility is more limited geographically.

If Airbnb list an apartment in London, this is useful to anyone, anywhere in the world travelling to London. Likewise, their demand side are travellers, so more travellers is useful to supply globally. If Uber list a taxi in London, this is only useful to people in London. Their demand side may travel to other cities, so there is some geographic scale, but Uber still needs to go and build local supply in each market.

The fact that Uber’s supply is commoditised and its network effect is very local causes two problems:

The network effects tail off really quickly

Because it’s a commodity, once I can order a cab in 5 minutes on Uber, it isn’t that useful to be able to order one in four minutes or three minutes. Adding more taxis, at this point, doesn’t create any new value for users.There is more competition

Uber had to compete fiercely with copycats in every new market it went into. In many markets (eg. China) it failed to beat established competitors. Due to the commoditised supply, you also end up with a recurring problem called multi-tenanting, where both the supply and demand side will use multiple apps simultaneously. Any new company with enough cash can quickly buy up drivers and customers through cash incentives. In London, if you speak to most drivers and passengers, they use Uber, Bolt and maybe another app like Freenow or Gett.

These two factors make marketplaces like Airbnb a much more capital efficient investment than marketplaces like Uber, and much more likely to be high ROI. You can see this if you compare their valuation to the amount of capital they’ve raised:

You can also see it if you look at profitability. In 2022, Airbnb generated $1.9B net profit on $8.4B of revenue. Uber lost $9.4B on $31.9B of revenue.7

2. Interaction Networks

Interaction networks connect users and enable interactions (information exchange) between them. This covers social networks like Instagram, but also the exchange of other types of information, like digital payments (Paypal, Venmo, Mastercard & Visa) and social gaming (Fortnite).

You can see that in terms of value, the same mechanics broadly apply. The most valuable interaction networks are linked to someone’s real identity, and their identity is a crucially important point of “supply differentiation”: It’s vitally important that you Paypal the right person money, but you can play Minecraft with whoever really.

The best interaction networks are also geographically agnostic, meaning that users in one geography can pull in users from other geographies very easily. You can’t go on a Tinder date with someone in Delhi if you’re in Berlin, but you can watch their YouTube video.

3. Data Networks

Data network effects are slightly trickier to identify, and a lot of startups will claim to have data network effects when they don’t. You see them in B2C (eg. Citymapper or Waze - where every new traveller adds data that makes the app experience better for other travellers) and also B2B (eg. UIpath, a robotic process automation company - where every company using the product adds training data that helps the product to work better for other companies). Google’s Search Engine is, in my view, a great example of a powerful data network effect, although when I chatted with Sameer he didn’t quite see it this way.

Again, the differentiation and geographic scale rules apply.

Data tends to be more differentiated if it decays (i.e. stop being useful) more quickly - i.e. you need a constant fresh supply. For example, vehicle traffic data from yesterday doesn’t tell you much about what traffic will be like today. So having that constant fresh supply is a competitive advantage. Whereas old training data for eg. a search engine or a language model is still useful - i.e. doesn’t decay.

However, differentiated data is also much more likely to be local in nature. There aren’t many examples of rapid decay data that is also collectable and useful globally. So there are very few businesses with data network effects that sit in the highly attractive top right quadrant.

4. Platforms

One of the first and greatest platform businesses in the world is Microsoft, and Bill Gates’ definition of a platform is pretty on the money:

“A platform is when the economic value of everybody that uses it, exceeds the value of the company that creates it.”8

When you create a true platform, multiple valuable businesses are built on top of that platform.

The Windows operating system was one of the first - numerous billion dollar software companies built software exclusively for Windows. Apple IoS and Google’s Android are very obvious modern examples.

Here’s an interesting point: in general, network effects can only take hold when a product has reached a minimum threshold or critical mass of users (also called liquidity) — this is true for marketplaces, interaction networks, and data networks. Nobody would use WhatsApp if other people didn’t use it. Getting to this critical mass is known as the “cold start problem”, and there are a variety of ways to address it, which we won’t explore today.

Platforms are a bit different. They tend to be built on top of another product with existing adoption, which often in and of itself does not exhibit a direct network effect. That is to say, they already have liquidity, and they then build a layer of value on top of that liquidity that creates a network effect.

For example, Salesforce started out as a simple SaaS company, with high embedding but no real network effect. They built all the software that their customers were using in-house. However, at scale, Salesforce was able to create a developer ecosystem and encourage third parties to build apps and integrations for Salesforce. Salesforce was letting these third parties sell to its users, and taking a cut. At this point, Salesforce became a true platform, and its ability to reach more customers and drive additional revenue began to increase rapidly.

Sameer also compares platforms on two axes, but they're different (i.e. not geographic scale and supply differentiation):

Integrations vs Apps

Weak platforms have integrations with valuable companies - for example, Slack integrates with Airtable, but Airtable is not built on top of Slack. Strong platforms have apps - King, the developer of Candycrush, acquired by Activision-Blizzard for $5.9B in 2016, built its business fully on top of iOS and Android, developing apps to sell to their users. Other network effects businesses (eg. Uber, Snapchat) are built wholly on top of these platforms!Focused vs. Multi-purpose

Lower value platforms tend to be more focused - so eg. Sony’s Playstation is pretty much limited to the gaming market, whereas in China, people build lots of different products on top of WeChat - you can order a taxi, shop, chat and much more.

ChatGPT and other foundational AI models have the opportunity to transform from being businesses with a relatively weak data network effect (based on slow decay human feedback data training its model) into platforms. This is why VCs are so excited about them. Which AI companies manage to get people building true apps, rather than integrations, may well be the measure of success.

If you can build a true platform, you can really start to make money.

I suspect that what Elon is doing with X / Twitter is essentially trying to turn it from an interaction network into a true platform. I’d expect to see more opportunities for people to build value on top of X, with X taking its cut.

We’ve covered a lot of ground today. It’s been a bit of a whistle stop tour. I highly recommend that you check out Sameer’s excellent blog if you want to continue exploring this subject. The resources on NFX Capital’s website are also excellent, and even more detailed.

If you’re interested in investing in network effects businesses alongside Sameer on Odin, sign up below:

I’ll leave you with one parting thought - what comes up must come down. One of the other things you notice with network effects is that they can work in reverse just as quickly, driving rapidly declining utility and product abandonment.

Their biggest strength can also be their greatest weakness, so you need to be really thoughtful when you back businesses in this space at any stage. I haven’t done enough thinking yet on where this is most likely to be the case and why, but you see it with eg. social networks a lot. Interesting.

Catch you next week ✌️

PR

AT&T was eventually broken up, in 1984, into a number of regional companies.

Interestingly, the breakup didn’t really achieve much - the “Baby Bells”, as they were known, have gradually re-consolidated into a duopoly - Verizon and (the new) AT&T - and bought up more competitors and other networking systems (cellular, satellite) in the process. Network effects make this somewhat inevitable - these systems *want* to consolidate, because it makes them more efficient.

This piece by Trung Phan about Berkshire Hathaway’s bet on Apple is great.

If you want to read more about the history of the silicon microchip, how chips are made today and why they’re likely to be at the centre of the major geopolitical conflicts of the 21st century, I highly recommend Chip War by Chris Miller. I’ve mentioned it in a previous blog post - it’s a great read. Thanks Kaysan Nikkah for lending me it!

See the section on defensibility in the digital age in this video

To some extent, software companies with network effects appear to actually invert the traditional economic law of diminishing marginal returns to scale, where as you get bigger at some point you produce less profit per dollar spent.

That is to say, software companies with network effects have increasing returns to scale without a clear end point - as they get bigger, they produce more and more profit per dollar spent. Every new user adds output, and the additional cost of the input - replicating the software - is marginal.

There is, of course, a natural ceiling to this, because there are only so many humans on earth to use your product, so eventually it has to look more like an S curve. You would imagine that the big guys are in fact pretty close to the top of that S curve, but who knows!

70 Percent of Value in Tech is Driven by Network Effects - James Currier, 2019

From an interview between Semil Shah and Chamath Palihapitiya where he explains why Facebook isn’t a platform in the same way that Microsoft is. See Stratechery for more.